When does a hill become a mountain? Our expert guide to what makes a mountain, a mountain

We delve deeper into the topic of many long debates: what constitutes a mountain? Or when is a land mass a hill and when is it a mountain?

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of the biggest debates among outdoors people – whether they hikers, trail runners, climbers or mountaineers – is when is a mountain, a mountain and not a hill? What then it becomes clear, after some discussion and a check on-line, that there is no official, universal definition of what constitutes a mountain, rather than a hill.

For sure, there are mountains that are definitely mountains. Likewise, there are hills that are definitely hills. However, somewhere in between are land masses that defy consistent categorization. Should hills and mountains reach a certain height at their summits? Is it the volume of land that creates a mountain, rather than a hill? Or are there different classifications for hills and mountains depending where you are in the world?

The verdict: when does a hill become a mountain

I believe that attempting to quantify what's hill or a mountain using mathematics is completely pointless.

Alex Foxfield, Mountain Leader

A mountain is high, prominent, steep, rugged, rocky and relatively inhospitable. It requires a certain degree of challenge to gain the summit.

A hill, in contrast, is lower, less prominent, has more gradual gradients, with grassy terrain and has a more hospitable terrain. It requires a smaller amount of challenge to summit.

These descriptions can be generally a good guide for defining a mountain and a hill.

There is one mathematical definition from the United Nations Environment Programme that takes into account height, slope angle and prominence but it's complex and the above definitions are more easily understood.

In Britain, it is widely assumed that a hill is less than 2000ft tall, while a mountain is more than 2000ft in height.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

But, it seems to us, trying to categorize a hill or a mountain in terms of summit height or total land mass – or any kind of math-based analysis – is seemingly arbitrary because there are so many landscape variances across the world. For example, there are there are cities that are at a higher elevation that some country's highest peaks.

We think that a mountain is more about its character than its height – and this is based on personal judgement. In other words, one person's mountain is another person's hill. The best news is that whether you call it a hill or a mountain, many of these land masses are great for a walk in your favourite hiking boots.

The metrics...

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Hill | Mountain |

Height | Less than 2,000 feet (according to many British organisations) | More than 2,000 feet (according to many British organisations) |

Prominence | Rising gradually from the land | Projecting conspicuously above its surroundings |

Gradients | Gentle | Steep |

Character | A rounded elevation of land | High, rocky and a challenge to climb |

Terrain | Grassy, perhaps wooded or utilised for housing, agriculture or energy use | Rocky and potentially glaciated |

The movie: The Englishman who went up a hill...

In the 1990s, a movie, The Englishman Who Went Up A Hill But Came Down A Mountain, told the story of a young cartographer (a mapmaker) sent to re-measure a peak in Wales.

When the initial calculations by the cartographer (played by actor Hugh Grant), ‘lowered’ the summit to below the 1000ft threshold required in Britain at that time for mountain status, cunning locals waylaid him while they added soil and rock to the top, effectively rebuilding their hill back to a mountain.

The movie is a work of fiction but it highlights the pride that communities take in living next to a mountain. It's suggested that anyone can climb a hill, but it takes a certain fortitude to put on a backpack to climb a mountain.

In addition, the Welsh "mountain" was defined by its height above sea level alone and did not take into account any other important criteria, such as profile, prominence, isolation, terrain and steepness.

All this said, some people do want to know what constitutes a mountain...

A mountain: the dictionary definition

Consult the American-English Merriam-Webster Dictionary and it will tell you that a mountain is: "A landmass that projects conspicuously above its surroundings and is higher than a hill." So, it seems, prominence is of key importance.

A mountain must first "project conspicuously" but how high is a hill? In another American-English Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition, we discover that a hill is: "A rounded elevation of land lower than a mountain."

But neither definitions explain exactly what a hill is, nor what a mountain is.

In the Oxford English Dictionary, a mountain is: “A natural elevation of the earth’s surface rising more or less abruptly from the surrounding level and attaining an altitude which, relatively to adjacent elevations, is impressive or notable.”

Again, there is no detail of height or prominence, although now there is a greater description of the shape of a mountain.

In the Cambridge Dictionary, a hill is described as: "An area of land that is higher than the surrounding land– hills are not as high as mountains." While a mountain is: "A raised part of the earth's surface, much larger than a hill, the top of which might be covered in snow."

Now, it's seems, a mountain requires snow to be a mountain.

And so the picture grows of what makes a mountain a mountain but still there is no clear definition.

The idea or concept of what is a hill and what is a mountain might be clearer, but perhaps the definition should be left to geographers rather than lexicographers. Yet, even among physical geographers, there does not seem to be an agreement on what constitutes a mountain and what constitutes a hill.

When does a hill become a mountain in the US?

National Geographic states that: "Hills are easier to climb than mountains. They are less steep and not as high." This brings into the picture a degree of effort required by a hiker to ascend a hill or mountain.

Does that mean that if you need trekking poles or sturdy hiking boots, rather than "only" trail shoes, that you are on a mountain and not a hill? The issue with this definition is that not everyone's fitness level is equal and there are other factors, such a hiking in winter conditions and the type of terrain you encounter. You might also make the ascent more challenging by running it, rather than hiking it.

The US Geological Survey doesn't help much either, reporting that there's no official difference between hills and mountains. At one time, both the United States and the United Kingdom defined mountains as summits over 1000ft in elevation, however this distinction was abandoned in the mid-twentieth century.

How tall does a hill have to be become a mountain in the UK?

In the UK, it's widely suggested by many walking groups and official organisations that a height of 2,000 feet (610m) is the threshold beyond which a hiker steps from hill to mountain. Although, in global terms, this altitude is very small compared to the great mountains of other areas, such as the Himalayas.

Also, it you take a closer look at some so-called hills in the UK, they seem far too lofty to be classified as "just" hills. For example, the rocky fist of Haystacks in the English Lake District is 13 meters shy of the stated height, yet it is much more of a mountain than many gentle, grassy uplands in the region, that just so happen to have much loftier summits. The point here is that there can be high hills and low mountains.

As you can see, we are getting nowhere trying to define a mountain by height alone. A mountain must also have a certain amount of prominence, its sides must be sheer, its terrain rugged and its summit set apart from others.

Suilven, in the far north of Scotland, is a good example of this. It falls short of the two most commonly used Scottish mountain classifications: it's not a Munro (a mountain over 3,000 feet) or a Corbett (a mountain between 2,500 feet and 3,000 feet). Instead, at 2,398 feet (731 m), it has to settle for being a Graham – and many people consider Grahams to be hills. Yet, Suilven rises so defiantly from the surrounding landscape, with such savage architecture that it defies you to call it a mere hill. Therefore, Suilven must surely be called a mountain.

What does prominence have to do with it?

Perhaps, then, a mountain has less to do with height and more to do with prominence and character. A clear illustration of this is the Bolivian city of La Paz, the highest capital city in the world at 11,942 feet (3,640 m). This is much higher than the highest peak in many countries, but we're not suggesting the 750,000-plus population of La Paz live on top of a mountain. This is because the city is built on lower ground than much of the surroundings landscape and it is also dwarfed by the distant Mt Illimani, which towers to 21,122 feet (6,438 m) above sea level. Now that's what everyone would call a mountain!

Prominence is defined as the elevation of a mountain summit relative to its surrounding terrain. The city of La Paz, while at great elevation, has a negative prominence because it is surrounded by higher land, so it could never be called a mountain.

Mount Scott in Oklahoma has bagged itself mountain status by stretching 823 feet (251m) from base to summit, despite topping out at only 2,464 feet (751m) above sea level. In this context, Kilimanjaro is arguably more of a mountain than Everest, given that it soars from the surrounding plains, rather than merely reaching higher than its subsidiary peaks.

However, just like overall height, prominence alone does not forge a mountain. Everest, which has recently been calculated as even taller than once thought, is far more a mountain than Kilimanjaro thanks to all its other characteristics.

What are the characteristics of a mountain?

Could it be that the best definition of what makes a mountain a mountain is its character when compared to a hill? A hill conjures up images of gentle, green slopes. Getting to the top of a hill should take some effort, but not pose too many challenges or take the best part of your day to achieve.

A mountain, however, should be more of a challenge, both physically and in terms of resources – you'll need your day pack at least. The terrain should be craggy in places, or forged from rock.

The classic image of a mountain is one of rugged beauty with glacier-forged combs, crashing waterfalls and pointy summits. You can stand proud on a weather-scoured summit in the far north that may be only a fraction of the height of a gentler but much higher upland regions in the south, yet you will be in no doubt that your feet are planted on a mountain.

You could even argue that the weather can transform a hill into a mountain, adding a layer of challenge, such as snow and strong winds, that is not present in the warmer months.

Call something that has the character of a mountain a hill and you may incur the wrath of those who love the wild places. The Cuillin Ridge on Scotland's Isle of Skye is the guts of an ancient volcano. The range is characterised by jagged peaks, black rock and dizzying exposure. The Cuillin are undoubtedly mountains, despite their relatively diminutive height when compared to the Rockies, Alps, Andes or Himalayas.

At some point, they became labelled as the Cuillin Hills, probably by someone who didn't know any better. In his book, 'The Cuillin – Great Mountain Ridge of Skye', Gordon Stainforth lambasts this error, saying: "The originator of this travesty should have been swung on the end of a long rope from one of the many high and very un-hill-like points that are to be found on the Main Ridge."

The distinction between a hill and a mountain can make people very passionate indeed...

Mountains or hill: beyond sea level...

Definition pedants may even question why sea level matters. The tallest mountain on Earth measured from toe to top is Mauna Kea, an inactive volcano in Hawaii, which reaches skywards for 33,474 feet (10,203m). Does it matter that only 13,796 feet (4,205m) of Mauna Kea rises above the Pacific Ocean? Well it probably does to those that reach the summit of Mount Everest, the acknowledged highest point on Earth at 29,029 feet (8,849m).

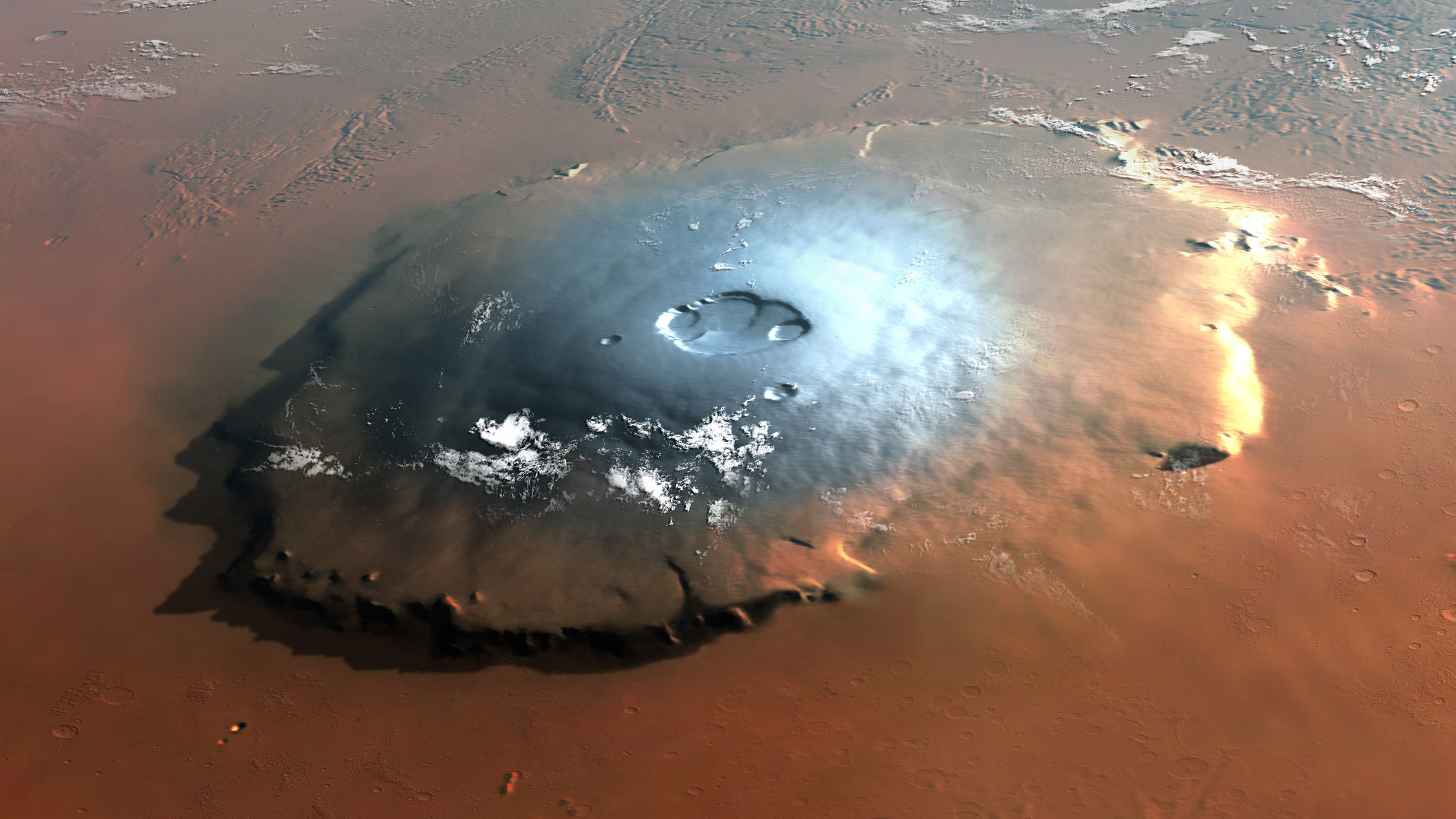

Yet in this poker game of height, Olympus Mons on Mars sees Everest’s peak and raises the stakes to 69,459 feet (21,171m). As everywhere in life, in this contest there’s always something bigger, better and more impressive.

The United Nations definition

Perhaps the most comprehensive set of mountain definitions come from the United Nations Environment Programme, which established different topographical criteria for a landmass to meet.

Basically, any peak above 8,200 feet (2,500m) is a mountain; as is any outcrop of 4,900-8,200 feet (1,500-2,500m) with a slope of at least 2°; as is a peak of 3,300-4,900 feet (1,000-1,500m) with a slope steeper than 5° or a local elevation range above the surrounding area of at least 300m for a 7km radius. Even a hill of 1,000-3,300 feet (300-1,000m) that stands proud of its surrounding area by 300m can claim mountain status.

It's all rather mathematical and quite a lot to take in, don't you think?

An attempt to define exactly what makes a mountain with maths will always be flawed. It is subjective and a blend of various competing factors: elevation, prominence and character. Above all, unlike Hugh Grant, the message is clear – whatever hill you climb, remember when you get back to tell people it was a mountain.

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com