"Getting chewed on sucks": I fought a grizzly bear and won

Read the harrowing account of how one man fought off a grizzly bear, and what he learned from his recovery

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

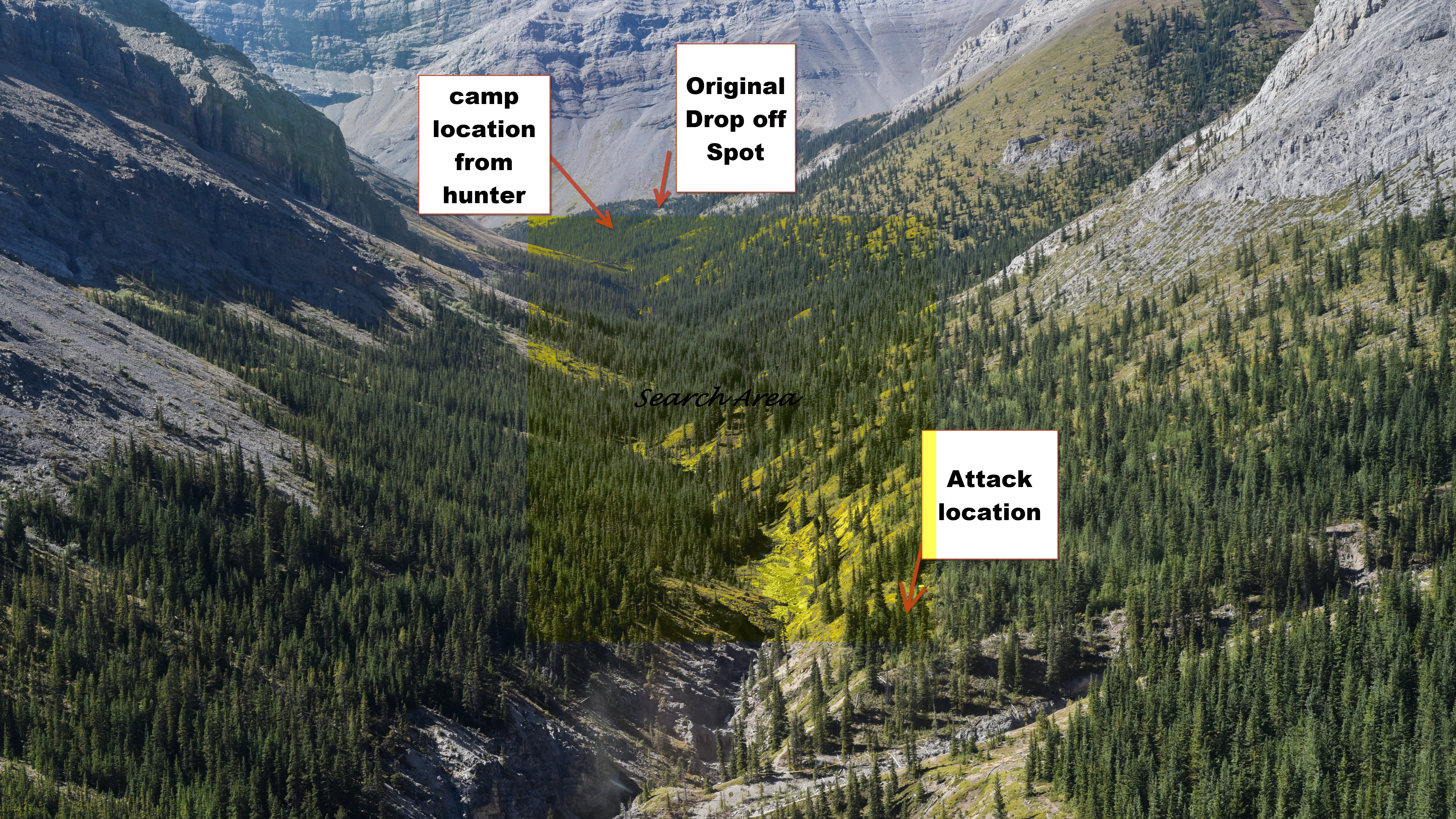

For hunter Jeremy Evans, the morning started out like many others in his 17-year quest to bag himself an elusive bighorn sheep. It was August 2017 and the Alberta resident had left the house in his truck at 3am, parked at a remote trailhead and ridden his mountain bike nearly nine miles into the mountains to find a quiet spot to scope out a good hunting spot for the season. Soon, he spotted some bighorn sheep and was watching them through his binoculars when he saw the blur of a small brown creature that was definitely not a sheep cross his path.

“I knew right away what it was. It was one of those moments where I was like, ‘oh crap, where’s momma?’” he recalls.

Evans quickly reached down to his backpack to grab his bear spray. He’d usually carry it in an easily accessibly chest holster, but admits that in the excitement of that morning, he’d packed away instead – a mistake that should have cost him his life.

He heard a noise behind him and a glance over his shoulder revealed that momma, aka a very irate grizzly bear, was just a few feet away and charging towards him.

What happened next is a truly horrifying encounter which makes Leonardo DiCaprio’s tussle in the 2015 film The Revenant look like child’s play. If you’re faint of heart, you might want to stop reading, not least because Evans remembers his prolonged battle with the grizzly, which resulted in catastrophic injuries to his head, hands and leg, in astonishing detail. When I go back to the recording of our interview, I realize it takes him a full 10 minutes just to tell this part.

It goes something like this:

The bear charges Evans. Evans throws his bike in its path. Grizzly gets her head caught in the frame. He grabs his backpack and starts beating her over the head with it. She crushes his hands against the metal frame of the pack. He manages to get the bear to back away about 30ft while he struggles for his gun or bear spray.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Before he’s able to reach either weapon, the bear charges again. He starts running up the mountainside planning to jump off the slope and into a tree. Extraordinarily, he manages it, but the bear, who has given chase, grabs him by the right leg and sinks her teeth in. She pulls him down from the spruce tree, bites into his torso and throws him six feet. Next, she bites into his head.

At this point, Evans is following the common guidance of what to do if you meet a bear on the trail and playing dead, but soon, he realizes this strategy isn’t working out so well for him.

“After the first bite I was like, screw this, getting chewed on sucks. It’s really hard to play dead,” he laughs.

Evans rolled over and started punching the bear in the face and jabbing at her head. When she came down for another bite, he managed to shove his hand down her throat, grab her tongue and incite the gag reflex, another technique that’s purported to be an effective evasion tactic if a bear gets close enough. He reached for the bear’s crotch, grabbed whatever he could and twisted hard; with a squeal, the grizzly took off.

“I stood up right away, dusted myself off and got to my pack where I took a picture of my face.”

The picture, which I’ve seen and I can testify is the stuff of horror movies, revealed half his face was gone. Evans leant up against a tree stump, went for his gun again and was loading up his clip when he heard a strange sound, given that it was the height of summer.

“I heard the sound of ice breaking and my hands went numb and dropped to the side of me.”

It wasn’t ice breaking. It was the sound of teeth crunching his skull. The bear was back, had clamped her jaws around the back of his head and dragged Evans backwards once again and was chewing away. At some point, she let go and Evans fell back onto the earth with the bear on top of him. He reached up and grabbed what he could, locking himself into the bear in a way he describes as being like a UFC fighter, which caused the bear to panic and take off once again, towards her cub.

This time, she didn’t return. He was alive, barely.

“I was just able to stay calm and make rational thought decisions,” says Evans, who credits that ability with his survival, warning others to always plan for the worst.

“Always be prepared for the unexpected. Make sure you keep your bear spray where you can actually reach it. Practice.”

The attack was over, in reality probably taking less time than he’s taken to describe it to me, but Evan’s battle had really only just begun.

“After she left, I couldn’t stand up, I couldn’t see. I knew relatively where I was on the hillside and I knew I had to crawl down the hillside to get to the trail.”

It might all sound unlikely, but photos of his face, the scene of the struggle, and a hastily written note to his wife telling her he loves her all confirm Evans’ account. He somehow found his backpack and rifle, despite having one eye dangling out of the socket. Scrabbling around in the first, he discovered the remains of his face.

“What do you do in that situation? You know you’re not going to make it,” remembers Evans, who confesses in his 2022 book on the event, Mauled: Lessons Learned from a Grizzly Bear Attack, that upon finding his gun, he attempted to end his life.

“I did put the gun in my mouth and I did pull the trigger, but it didn’t go off.”

With the attempt failed, Evans decided to try to make his way down the trail so there was a chance of someone finding him, firing his gun at every dark shadow. What follows is an epic journey of crawling down a steep slope, falling into multiple gullies, and up the other side. At some point, he has the idea to play some music on his phone as a distraction and finds himself scrambling down the hillside to the tune of Baby Shark, which he and his wife had been using to lull their newborn daughter to sleep.

“That gave me a little bit of the willpower to get out because the song’s so annoying.”

It’s hard not to think that his survival in part comes down to being of that special breed of hardy foot soldier that comes part and parcel with being from the vast wilderness of the prairie provinces, where grizzlies are common. But he says it’s due to being able to strategize his mission.

“When you’re in a situation like that, think of small attainable goals,” he advises. “If I would have tried to make it to the truck, I probably would never have made it to the truck. I was thinking, ‘Can I get to that next trail? Can I get to that next tree?’ and when you achieve those little goals it gives you, I guess, a sense of accomplishment and you can keep moving on.”

Against all odds, Evans got himself to his truck and somehow drove himself to a vacation camp where horrified holidaymakers called for help. Twelve hours after the attack, he arrived at a hospital where he regaled the medics with an impressive ability to see the funny side of things. The doctors and nurses, inexplicably, wanted him to rate his pain scale from one to 10, which is usually a question reserved for trying to assess the severity of a situation. It seems unnecessary given the state of the patient, and clocking this, he claims he simply responded:

“Unbearable.”

But unsurprisingly, recovery was no laughing matter. Evans remained in the hospital for five weeks, eight hours and 23 minutes. Once he was in the hands of doctors, it’s a story of the wonders of modern medicine, but it also presented the most challenging part of the story.

“Physically, I’m around 95% of where I was pre-bear incident,” says Evans, optimistically I think, when he starts listing the damage. Loose tendons on his right leg, eyelids that don’t close causing pain and dryness.

“But I can live with that. The fighting the bear part and crawling out was the easiest part of the whole thing. The hardest part to get over was the PTSD, the nightmares and the flashbacks that happened after. That was the roughest part, I don’t wish that upon anybody.”

Constant nightmares and flashbacks plagued Evans for the next fours years, and it was only after a particularly traumatic incident at home that he realized he needed more help. He finally received relief from the PTSD in March of 2022 after undergoing several sessions of accelerated resolution therapy, which reprograms the way traumatic memories are stored in the brain so that they no longer severely trigger the patient.

“I did one 45 minute session and that was the first time in four years that I've slept for seven hours. That was life-changing,” he says, adding that seeking help for mental health was one of the most important lessons he learned, and one he hopes to encourage in others.

“Asking for psychiatric help is not a sign of weakness, it’s a sign of strength. You don’t have to be a big strong guy and try to hold it all in. You can’t do it alone.”

Today, other than three or four minor flashbacks or night terrors in the past year, Evans’ life pretty much looks like it did before the attack. He goes to work as a maintenance supervisor at a food manufacturing facility (he returned seven weeks after the attack), he does lots of interviews like this one, and was back to hunting the weekend after he left the hospital. He finally shot a bighorn sheep the following year.

“I’m not one to sit around,” he laughs.

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.