Heat? Hypoxic tents? Breathwork? How best to train my body before tackling the high-altitude trails to Everest Base Camp

Adventure staff writer Julia Clarke reveals what she’s doing to prepare for oxygen deprivation during a Himalayan trek

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By the time you read this, I’ll be high in the Himalayas, trekking to Everest Base Camp. The 80-mile trek takes 11 days and gains around 8,000ft (2,438m). There are a lot of unknowns to venture into with this next chapter in my storied hiking career, but one thing is for sure: the air will be thin.

As we climb higher, air pressure will go down, and that means the oxygen particles in the air are spread more diffusely, which means I get fewer in each breath. This induces a state known medically as hypoxia, and ideally, my body will increase hemoglobin levels (red blood cells) to help deliver more oxygen to my muscles to offset the effects. If it doesn’t, I’ll suffer the effects of altitude sickness, something I’m eager to avoid.

High altitude and I do have plenty of history. For over a decade, I lived in a Colorado ski town at 8,000ft (2,400m) above sea level and my adventures there frequently saw me venturing higher than 14,000ft (4,267m).

At that elevation, I know that regular hiking feels harder. My breath is more labored even when the trail doesn’t seem all that demanding. My fingers swell up. Living, working and playing at altitude for such a long time meant I became well-adapted to it. But that was then.

A flatlander once more

For nearly five years now, I’ve been living back in Scotland, which, mountainous as it may be, caps out at a measly 4,413ft (1,345m) above sea level on the summit of Ben Nevis. High enough to have big adventures? Sure. But no training ground for serious altitude.

At 17,598ft (5,364m) above sea level, Everest Base Camp is some 3,000ft (914m) higher than I’ve ever been in my life, and we’ll spend just two nights in Kathmandu before flying to the mountains to begin our trek. There is no magic pill for altitude adaptation (well actually, there is, it’s called Diamox, but according to the pharmacy I’m not eligible for it) so I need to look elsewhere for help.

Early on, when I was invited to join EverTrek on the trip, there was talk of me preparing sleeping in a hypoxic tent, but I share a bed with someone I like. And besides, when I asked mountain guide Jon Kedrowski about them, he told me they may make no difference.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

“I’ve seen people use hypoxic tents, and they come to altitude and they get sick anyway, and it doesn’t work,” says Kedrowski, who’s been guiding treks to Base Camp for 10 years.

The best thing I can do, he says, is get myself back to Colorado. Kedrowski has just finished guiding a group to Base Camp, and tells me several of his participants from the East Coast spent 10 days out in Colorado with him beforehand, climbing 14ers to prepare. It worked, but sadly, a trip to Colorado was impractical for me this spring, for various reasons.

I sighed. And that reminded me – could breathwork help?

Just breathe

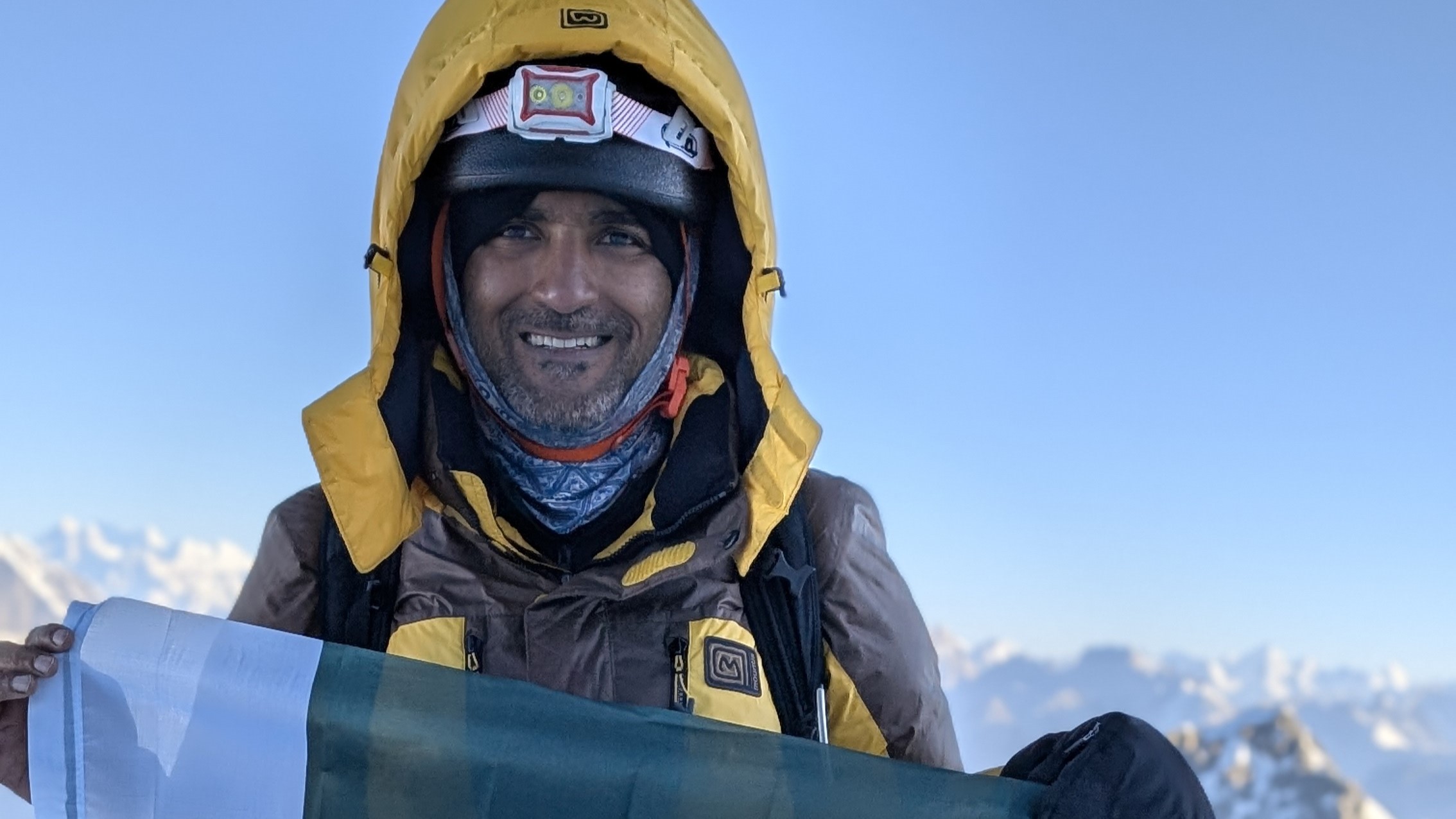

Last year, I interviewed a mountaineer named Umer Latif, who climbed Khusar Gang, reaching nearly 20,000ft (6,096m), after only three days of acclimatization. His secret weapon? A five-week High Altitude Breathwork Training program developed by a US-based company Recal Travel, during which Latif performed short breathing exercises to try to improve his VO2 max.

It may sound unlikely, but this approach is backed by some science – a 2012 study found that slow deep breathing improves oxygen efficiency and reduces systemic and pulmonary blood pressure at high altitudes.

As a long time yoga practitioner, this sounds more like it, and fortunately, this is a practice I’m already experienced in, so I've been implementing ancient deep breathing practices regularly for the past six weeks in the hopes of priming my cardiovascular system for what's to come.

Turn up the heat

Just when I was wondering if breathing deeply will be enough to fuel me as I head towards cruising altitude without a pressurized cabin, I remembered an article I wrote about heat training.

Brian Maiorano, an endurance coach who trains people in using the Core Body Sensor, told me that just like training at altitude, training at a warmer core body temperature increases hemoglobin, and that helps deliver more oxygen to your muscles.

“With altitude training, you obviously need to go somewhere where you're about 2,000 meters. With heat training, you can do it in your own garage no matter what the temperature is. If it's winter, you just overdress."

So a couple of months ago, I fired up my Core Sensor, synced it with my Coros Pace 3 watch, pulled on my Columbia Omni-Heat base layer and Montane Fireball Lite jacket, and hit the trail. It was early spring, so the outside temperatures were mild, and within 20 minutes, my watch told me my core body temperature had reached 101.8°F (38.8C °C). Rather than stripping off, I kept my layers on, and I’ve tried to train (hiking or trail running) in that zone for one hour, three times a week for the past six weeks.

For good measure, I’ve been putting in 15-minute sauna sessions several times a week as well. One 2022 study found sauna use had no additional benefits for hematological adaptations but a 2021 study found that it improved heat tolerance among middle distance runners, so I decided that, since I like saunas and have access to one, I might as well throw it in.

Will heat training help me handle the effects of high altitude? Only time will tell, but if nothing else, at least I’ve been slowly increasing my tolerance to discomfort, and I expect there to be some of that on the trail.

Ultimately, though, Kedrowski’s advice for handling altitude is probably the best answer:

“Really, just slow trekking, not rushing yourself, not carrying a heavy weight can be helpful. And hydrate a lot.”

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.