How to prevent altitude sickness: expert advice on how to stay safe when heading on high

We spoke to James Barber from the Altitude Centre - the UK’s leading altitude training specialists – about how to prevent altitude sickness, susceptibility to the illness, and potential remedies

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Of all the ailments and injuries that may befall a hiker while out getting their wander on, altitude sickness ranks among the most serious. While the most common symptoms that you might experience when venturing above the 2,500-meter mark – dizziness, shortness of breath, nausea, headaches, ataxia – are a mere inconvenience, all of these could prove precursors to (potentially fatal) high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high altitude cerebral edema (HACE) without due care and attention.

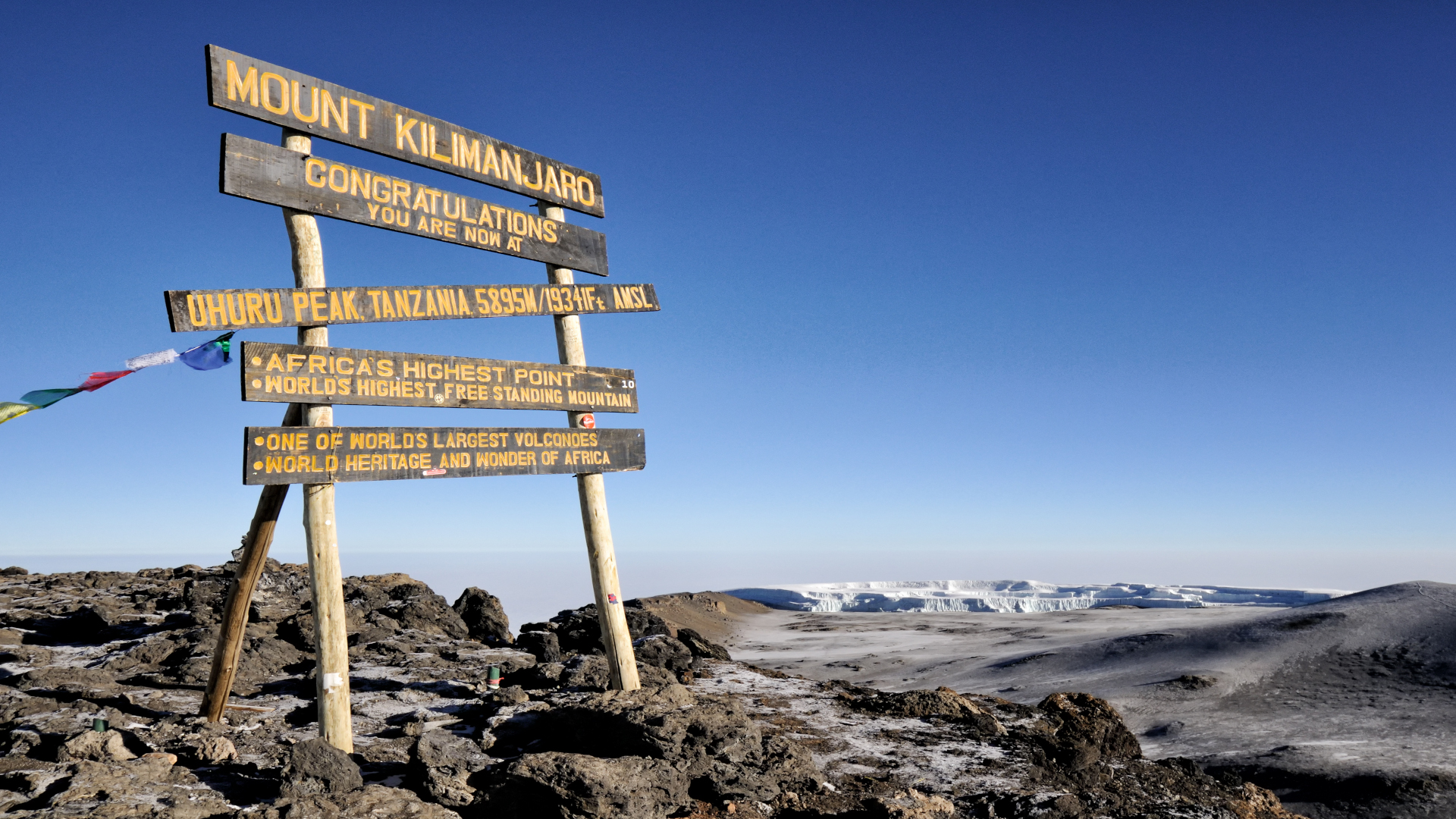

We wanted to know what actions we can take to ensure the risk of all of the above is kept to an absolute minimum, whether we’re out peak-bagging the Colorado 14ers, attempting to summit Kilimanjaro, or heading to the greater ranges on a high-altitude trek or mountaineering mission. To ensure we were getting the best advice, we spoke to James Barber from London’s Altitude Centre, a team of altitude training specialists who help athletes, mountaineers, and everyday adventurers alike realize their ambitions in oxygen-deprived environments.

Before we get down to our interview with James, let’s first take a look at the main take-homes from his advice:

How to prevent altitude sickness: at-a-glance advice

- Acclimatize, acclimatize, acclimatize! Whether you do this the old-fashioned way (ascending in 300-meter increments per day) or using the cutting-edge altitude chambers like those at the Altitude Centre, familiarizing your body with a hypoxic environment gradually is key to avoiding or lessening the symptoms of altitude sickness when it’s time to take on your ultimate objective.

- Different people react to high altitude in different ways – just because someone you know didn’t suffer symptoms at a certain elevation doesn’t mean you’ll be so lucky.

- If you’re based at low altitude, you should spend up to 6 weeks acclimatizing before your trip, depending on how high you plan on heading.

- Working on your fitness pre-trip can help you cope better with being at high altitude.

- Aim for no more than 300m of net vertical gain per day – this means you can hike more than 300 vertical meters in a day, but make your next sleep is no more than 300 meters above your last one.

- The main symptoms of altitude sickness are headaches and nausea. If these evolve into vomiting, ataxia, and sustained headaches, then descending to a lower altitude is the safest course of action.

- Diamox can help; the jury’s out on Ginkgo biloba; Viagra can improve your physical performance (on the trails, that is…), but won’t do anything to mitigate the symptoms of altitude sickness.

How to prevent altitude sickness: interview with James Barber

What can people do pre-trip to prepare for a hike or trek at high altitude?

A lot more than you might expect. The first misconception is that people tend to think it’s random whether they’re going to suffer from altitude sickness or not, but we can actually predict it to some extent. We have developed a way of testing people at high altitude prior to going to altitude, using simulated altitude and testing them both passively and during exercise on a treadmill to understand individual susceptibility to low-oxygen or hypoxic environments. From that people can then prepare nicely with simulated altitude training. We basically use technology that reduces the amount of oxygen that someone breathes, either in a chamber or with a mask-based generator. At sea level, 21% of the air that you’re breathing is oxygen. We can reduce that to, say, 15% for exercise training or down to as little as 9.5 or 10% for acclimatization. Just by breathing hypoxic air, whether while exercising or resting, you can start a safe acclimatization process and reduce the risk of developing altitude sickness. Combining that with general fitness preparation will help you cope a little bit better with the altitude.

Do people have different levels of tolerance to hypoxic environments?

Absolutely. There’s a large genetic component to it but it’s also highly trainable. Someone who lives at low altitude and has never been to altitude before is likely to be more susceptible than someone who has spent a lot of time at altitude in the past. What we see is that people come in for an initial assessment and learn that they are susceptible to altitude. They then spend maybe 4-6 weeks training a couple of times a week in hypoxic environments and improve massively. It is quite individual, which makes it hard to predict unless you have access to this testing.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Does the environment you’re hiking in make any difference?

Not so much. Different levels of susceptibility in different regions is mainly to do with what they’ve done in terms of their ascent profile. If you’re in London and you fly straight into Cuzco, then you’re straight in at 3000 meters plus, and that’s a real struggle for people. It would be more comfortable, say, going to Kilimanjaro and going more gradually to that kind of altitude. The only thing that might have a bit of an influence might be how dry the air is, because of dehydration. At high altitude, the air is drier so you start to feel the effects of dehydration a bit more, which can exacerbate some of the symptoms of altitude sickness.

What does a good acclimatization strategy look like?

If you take Kilimanjaro as an example, you’d ideally be looking at a 4 to 8-week preparation phase. It’s quite individual, so we’d always recommend starting with an assessment to understand your tolerance to hypoxia to begin with, then trying exercise at altitude – general fitness work, interval training, and strength training, which is really important for climbers and often overlooked. We’d also have people walking on a treadmill with hiking boots and a weighted backpack in a chamber at 2700 meters of altitude. Then we’ve move into a specific kind of training called intermittent hypoxic exposure. What that means is basically using a machine that we have on site that takes air from the room, reduces the amount of oxygen in it, and then feeds it through a tube that you then breathe through a mask. The air alternates between five minutes at altitude, between 4000 and 6500 meters, and five minutes at sea level. What we’re aiming to do is drop the amount of oxygen in your blood for those 5 minutes at altitude and then allow the blood oxygen to come back up when you’re at sea level again. It’s kind of like doing interval training, but for your lungs. This starts to change how you breathe. It teaches your body to deal with the lack of oxygen and become more efficient with oxygen so you can transfer more of it from the air into your lungs, from your lungs into your blood, and then ultimately from your blood into your muscles and your brain.

What advice would you give to people heading to do a hike at high altitude?

Allow yourself time to prepare before you go – we recommend 2 or 3 months of preparation. That varies depending on what your background is. If you’re going from completely sedentary to trying to climb Kilimanjaro or if you’re a regular marathon runner climbing Kilimanjaro your schedule will vary slightly. Once you’re on the mountain, you can’t do anything slowly enough – be purposeful in what you do, but ascend slowly. When we run trips, we always say look for no more than 300 meters net gain in a day. You could climb more than that in a day, but then come down to sleep at a lower altitude – this can be a useful strategy but it depends on where you are and what trek you’re doing.

What are the incipient signs of altitude sickness?

I think people hear real horror stories about altitude sickness and think they’re suddenly going to start having horrendous symptoms straight away, but it’s very much a progressive disorder. It will start with mild symptoms like headaches and nausea which you can generally treat with hydration (see Water for hiking: how much do you need to carry) or by taking painkillers to relieve the symptoms. If nausea becomes vomiting and if the headache persists for a number of hours, then you’ve probably got a bit of an issue developing. If it’s allowed to progress from there then you’re starting to deal with things like ataxia (lack of coordination) and shortness of breath at rest – those sort of symptoms are a bit more serious and can be indicative of high altitude cerebral or pulmonary edema developing. It’s really important to know that those are endpoints of the disorder, though, and that the really severe symptoms can be easily avoided by good preparation and also by good communication with a guide.

At what point would you advise people to turn around and head down to lower altitude?

When people are dealing with more serious symptoms that’s the point at which you need to start looking at descending because the risk is fluid build-up on the brain or the lungs, which are very serious. This will generally happen at much higher altitudes or with very quick rates of ascent or when people aren’t acclimatizing well, but the key is to not let it progress to that point in the first place. Prevention is 100% better than the cure.

Over the years, various treatments (Diamox, Viagra, ginko biloba) have been touted as potential cures for altitude sickness. Do any of these work?

Potentially. Diamox is the one with the most research. Doctors have quite varied opinions. Some will be happy to prescribe it and will understand that it probably works, either as a course of medication or just to relieve symptoms. The flipside of that is that, being a prescription drug for glaucoma, some doctors will say I’m not prescribing that because you don’t have glaucoma. I haven’t personally had to use it, but my opinion is that I’d rather have it with me and not need it than find that I needed it and not have it. When I have seen people use it, it does seem to have worked quite well for them. The main thing to be aware of with Diamox is that it’s a diuretic, so if you’re taking it then you must drink more water – a liter more per day, otherwise you’re exacerbating dehydration.

Viagra doesn’t have a lot of research behind it in this context, but beetroot juice does a similar thing in that is causes vasodilation (dilation of blood vessels) has some research behind it that suggests it might help physical performance at altitude but it probably doesn’t stop you getting altitude sickness because it can’t actually increase the amount of oxygen in your blood. However, it might help the delivery of what little oxygen there is to the muscles and the brain.

With Ginkgo biloba, there is some thought that there could be something in it. Research on it is mixed but there is research in favour of it. Essentially, I don’t think it’s going to do you any harm.

Former Advnture editor Kieran is a climber, mountaineer, and author who divides his time between the Italian Alps, the US, and his native Scotland.

He has climbed a handful of 6000ers in the Himalayas, 4000ers in the Alps, 14ers in the US, and loves nothing more than a good long-distance wander in the wilderness. He climbs when he should be writing, writes when he should be sleeping, has fun always.

Kieran is the author of 'Climbing the Walls', an exploration of the mental health benefits of climbing, mountaineering, and the great outdoors.