Cold water shock – what is it and how can you avoid it?

We take a look at the dark side of cold water immersion, plus how to prevent cold water shock on your next wild dip

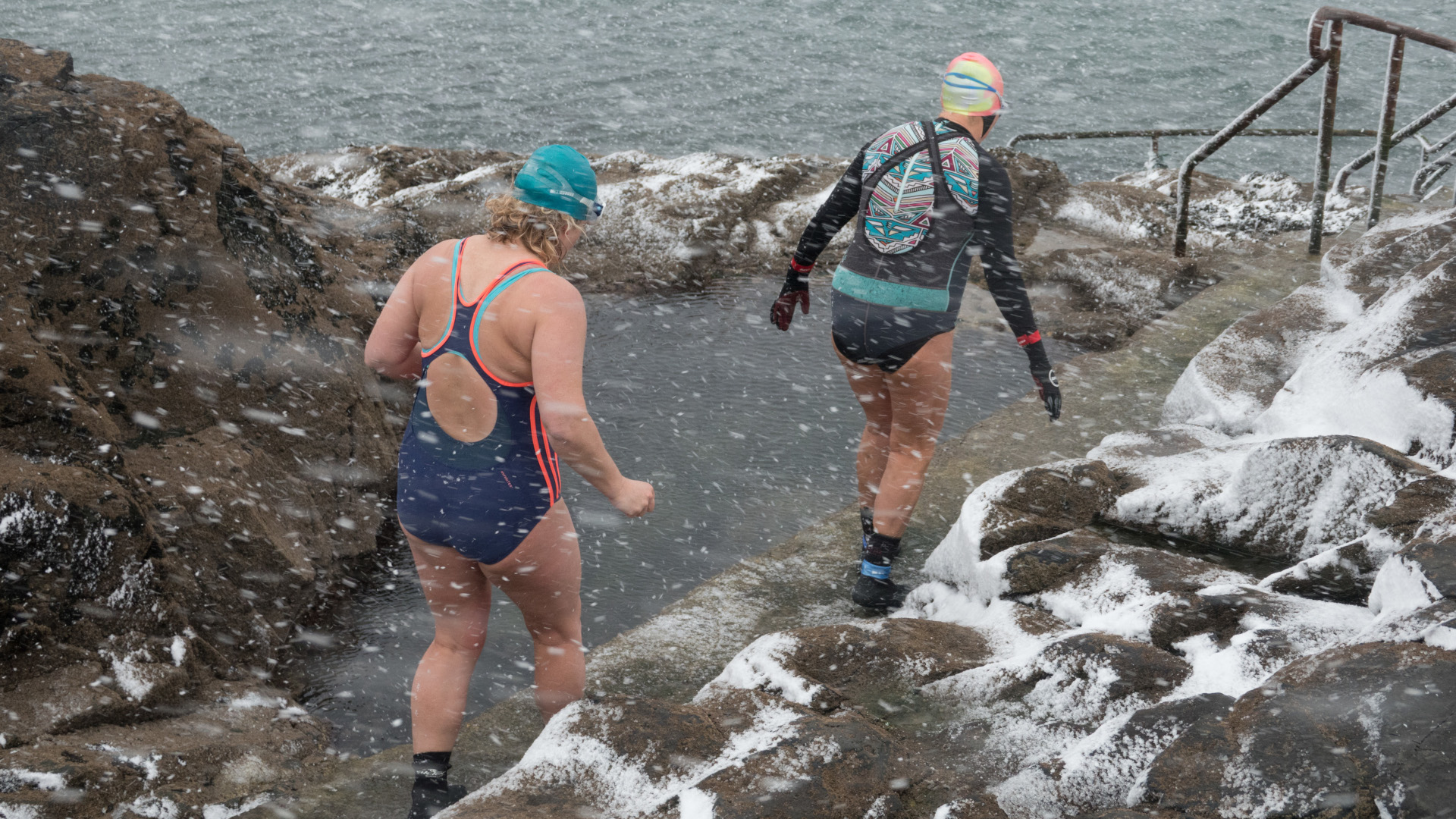

Recent years have seen a surge in brave adventurers plunging into icy lakes, rivers and oceans, seeking the benefits of wild swimming, reported to increase dopamine levels, lower blood pressure and improve mental health. While studies on wild swimming are scant, if nothing else, it is certainly invigorating and often takes place in some of nature’s most beautiful spots, so it’s no surprise that people are flocking to it. But as rates of wild swimming rise, so do the rates of an unfortunate statistic – deaths from cold water shock. In this article, we take a look at the dark side of cold water immersion, plus how to prevent cold water shock on your next wild dip.

What is cold water shock?

Cold water shock is the term for a natural, involuntary response to the body being suddenly submerged in water that has a temperature colder than 59°F/15°C. The physiological reaction may impede your ability to move once in the water, and also affect your heart and breathing. Cold water shock can lead to death through heart attack, drowning and hypothermia, and affects both strong and novice swimmers, as well as fishermen and people who fall into the water by accident.

Most cold water shock deaths are classified as drownings, so it’s difficult to get exact figures on the prevalence, but the summer so far has seen 18 deaths in Colorado’s waters and an unfortunate death in the icy waters of a lake just outside Yosemite National Park, while the UK reported 277 cold water-related deaths in the summer of 2021 alone. In the UK, Colorado and northern California, all popular hiking and wild swimming locations, water temperatures are more often than not colder than 59°F/15°C throughout the year.

What is the body’s reaction to cold water shock?

According to Water Safety Scotland, the primary physiological response of cold water shock is the constriction of the blood vessels in your skin upon entering the water. This forces your heart to work harder to get blood through your arteries and vessels, which leads to a rise in blood pressure that can ultimately cause a heart attack. If you jump or fall into water that turns out to be far colder than you were prepared for, another common response is of course to gasp. This can cause you to start hyperventilating and accidentally inhale water which can lead to panicking and drowning.

What are the four stages of cold water shock?

Cold water shock is the first of four stages of what is known as cold-water immersion leading to incapacitation and death. If you remain in the water after the initial shock response and don’t take measures to get your breathing under control (which we’ll discuss momentarily), the following stages may occur:

- Stage 2: Cold incapacitation, also known as swim failure, where you lose strength and coordination, making it impossible to swim or pull yourself to safety. This usually sets in within three to 30 minutes of entering the water.

- Stage 3: Hypothermia may set in after 30 minutes in the water, depending on your behavior, which is the medical term for a dangerous drop in body temperature which occurs when your body loses heat faster than it can produce it.

- Stage 4: Post rescue collapse, where your blood pressure drops and you lose muscle functionality, leading to cardiac arrest. This can occur before, during or after your rescue.

How to prevent cold water shock

As you now know, the key factors for cold water shock are the water being under a certain temperature, and you suddenly entering it. Naturally, cold water shock often occurs as the result of accidentally falling into the water, however it can occur when you intentionally jump in to cool off on a hot hike, or even during a wild swim. For both scenarios, there are steps you can take to reduce your risk and still enjoy open water swimming.

- If you’re heading to the coast, check the water temperature in the surf reports before you go in.

- Submerge yourself slowly, rather than diving in, to give your body time to adapt. Splash water onto your face as you enter.

- Wear a wetsuit suitable to the water temperature and your intended length of exposure, when the water is going to be colder than 59°F/15°C.

- Wear a flotation device when swimming to help keep you afloat. This might save your life if shock sets in.

- If you experience panicking and gasping, don’t try to swim straight away. Instead, roll onto your back and try to float, keeping your face out of the water and trying to extend your exhales to calm yourself down so you can call for help.

- If you’re able to, exit the water immediately and try to warm up quickly to avoid hypothermia.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.