How hiking boots are made: from design and materials to production and testing

We follow every step, from a twinkle in the eye of a designer to a trail-ready boot fit for the backcountry

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The complexity behind how hiking boots are made is fascinating. It’s easy to take a well constructed boot for granted and think of it as one single, fairly expensive unit. However, a hiking boot is a hugely complicated item, made from hundreds of components and various materials that all have to come together to provide comfort and protection for the wearer’s foot in inhospitable places. It's no wonder quality hiking footwear can cost a bit.

We demand more from our hiking boots than pretty much any other form of footwear. We expect them to keep us comfortable in backcountry environments that otherwise wouldn’t be. We expect them to grip effectively on muddy trails, snowy terrain and dry rock, while demanding that they keep our feet dry when crossing streams and marching through a deluge. So, how are these demands met? How exactly are hiking boots made?

Recently, we visited master Italian hiking boot manufacturer Aku’s HQ in the city of Montebelluna. As part of the visit, we ventured among the spectacular and jagged ramparts of the Dolomites, hitting the trails in Aku’s boots. We also learned all about the company's history, and its drive for quality and responsibly produced trekking and mountaineering footwear.

Importantly, we also were given a sneak peek inside one of Aku’s hiking boot factories and emerged with a new appreciation for the craft and art behind the creation of a hiking boot. Here, we reveal how hiking boots are made on a step-by-step journey from a boot’s inception to the finished article.

Last things first

Every hiking boot begins its life as a last, which is a solid, foot-shaped mold that determines the fit of the shoe. Every manufacturer has their unique lasts, which are often used on many of their models. So, while every last is different, two separate hiking shoes by the same brand might use the same last as their foundation. This is why all the best hiking boot brands are renowned for a particular fit. For example, Keen and La Sportiva are known for being kind to wide feet.

Aku’s primary last features opposite inclination at the heel and forefoot for a dynamic stride and, while its overall character remains the same, Aku have different versions of the last depending on the boot’s use. There’s Performance Fit, for technical mountain footwear like the Rock DFS GTX or the Tengu GTX; Anatomical Fit, ideal for trekking like the Trekker Pro; Precise Fit, for backpacking and medium difficulty terrain; Woman Fit, the clue is in the name; or Relaxed Fit, for leisure wear.

The design

Using the last as a template, designers create prototypes of the embryonic boot, often scrawling details of the upper onto tape applied around the last, or using computer software to simulate the look of the boot. Once the designers are happy, all the components have to be meticulously mapped around a virtual version of the last to check they all fit together. At Aku, one look at the computer mapping was enough to highlight just how many layers there are at work here and what an art putting a hiking boot together is.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

The raw materials

Many pieces of leather, synthetic microfibers, metal and rubber go into a single hiking boot and choosing the right materials for the job is important. Boot manufacturers source their components, such as metal eyelets and laces, from local businesses that have developed alongside them. This is the case in Montebelluna; the region is home to not just Aku but also fellow premium hiking boot manufacturers Scarpa and Asolo.

Car tires and hiking shoes have one thing in common: rubber. Grippy, durable, lightweight and waterproof, it’s the perfect material for taking on the backcountry. Brands either develop their own soles, while many opt for specialists like Vibram or Continental.

Leather is still the most common material used for hiking boot uppers, as it is extremely protective against Mother Nature’s occasional tantrums. She's often angrier in the mountains too. Leather’s characteristics read like a hiking boot wish list: robust, easy to shape, temperature regulating, breathable and hugely waterproof if treated correctly.

Its exact properties depend on which layer of skin is taken. Full-grain leather, made from the strongest part of the skin, is the most robust and durable. This is what most people imagine when they think of leather – smooth, strong and slightly shiny. Hiking boots often feature nubuck and suede, types of leather that are softer, velvety and more flexible than full-grain leather. Nubuck is the more durable of the two, as it comes from the top grain of the hide, and it is very breathable too. Suede is the fuzzier, soft side of the hide and isn’t quite as rugged as other types of leather.

Brands like Aku are experimenting with alternatives to leather, using recycled microfiber to lower the environmental impact of the chosen raw material. As well increased sustainability, these more modern fabrics are often lighter, though matching the durability of leather is still a tough ask.

Stitched up

Sheets of leather are cut precisely to fit the shape of the design. The position of the hide can be important here in terms of quality, while brands like Aku cut in such a way to reduce any wastage. Once cut, the pieces are sewn together on an industrial sewing machine by an expert. The upper is taking shape, but it’s not yet waterproof…

The waterproof membrane

Premium hiking boots are typically designed to be waterproof. An inner ‘bootie’ is stitched together using a waterproof membrane – Gore-Tex being the most renowned – as well as waterproof tape to cover the stiches. This membrane has tiny holes that let air escape but don't allow water through, making the boot breathable.

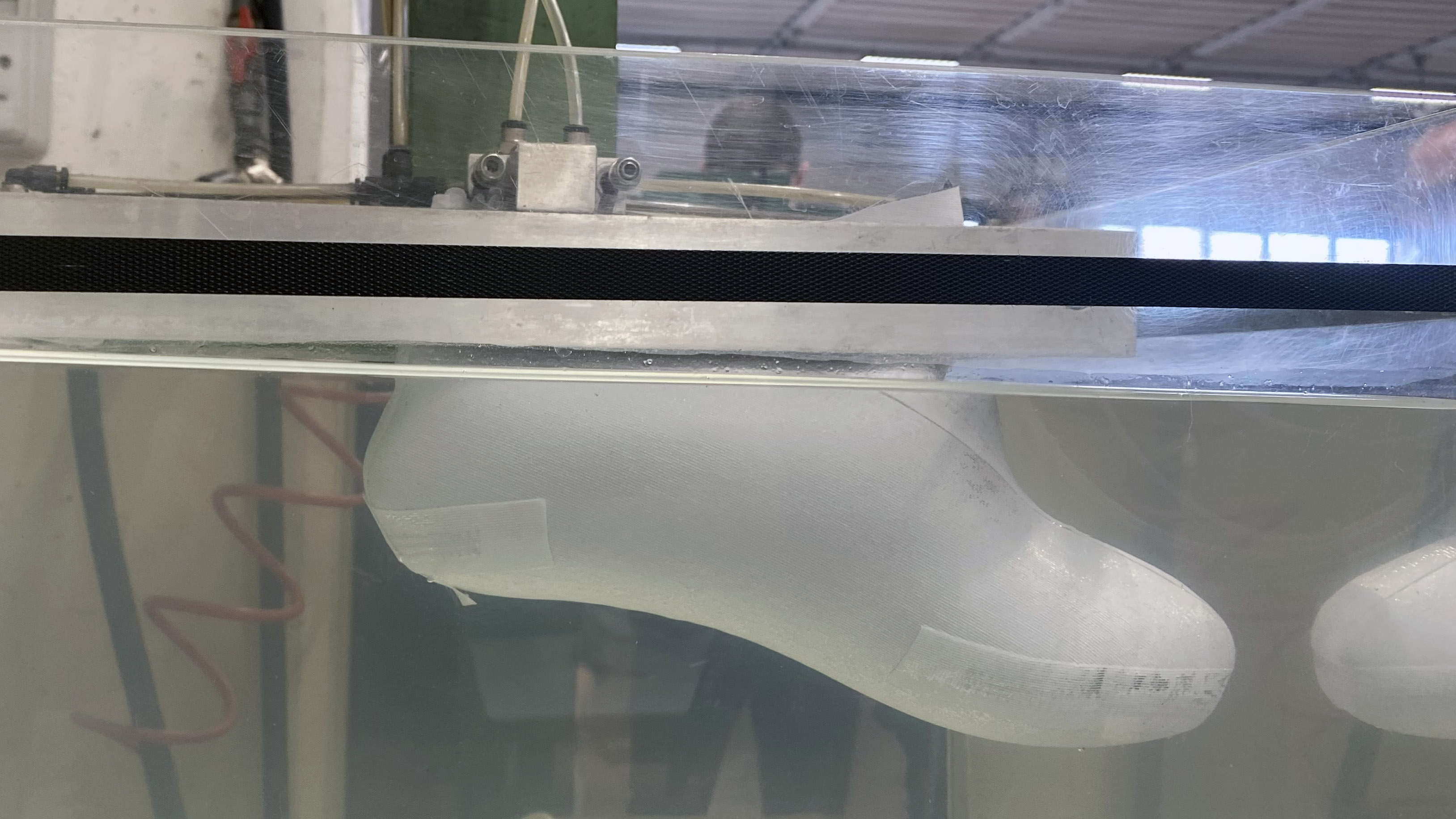

Once the bootie has been stiched together and taped up, it’s filled with air like a balloon and lowered into a tank to check that it’s watertight. Should it be compromised at all, air bubbles will rise from the bootie, signalling a dud. Otherwise, it’ll be given the green light for use in the boot.

Finishing off the upper

A mechanical press is used to fix the lacing system’s eyelets, D-Rings and/or speed hooks to the upper and cushioning is added, before the boot is then ready to be shaped and the lasting board attached. These days, this is usually done by a robotic device that holds the shoe in place, folds the upper’s fabric around the lasting board and midsole, before fusing everything together.

Heat and heaps of glue

It may seem odd that hiking boots, one of the toughest and most rugged items among the hiking essentials, are held together by glue. Of course, we’re not talking Pritt Stick here but super strong, industrial glue. Layers of the stuff are added to the bottom of the midsole, helping it maintain its structural integrity, before the boot is put into the dramatic-sounding “heat tunnel”.

After moving through the tunnel on a conveyor, the most robust boots are adorned with a rubber rand, which is applied by hand. Last but not least, the rubber outsole is fixed to the boot, first by hand and then by letting the machines take over to securely fuse it all together.

Of course, the boot is given a final inspection, polish, the rubber smoothed, the leather treated and any loose strands of thread or glue removed. Oh, and then the laces are added – quite an important detail we’re sure you’ll agree! Then, viola! A hiking boot has been born! From its embryonic, virtual days being rotated around by a designer in a computer programme to the end of the production line ready for the trails, it's been on quite a journey.

Testing, testing, testing

If you’re making something that your customer is going to climb mountains in, quality control is obviously paramount. The factory process isn’t finished at the finished boot, oh no. Samples are taken and literally put through their paces on an automated machine that puts them through thousands of watery steps. This allows an assessment of both their waterproofing and durability.

Things are taken even further with some samples, as they get filled with water and span in a centrifuge at around 250 revolutions per minute. This simulates up to ten times the pressure and wear that would usually be placed on the boot, testing its construction to its limits. If you were to ever return a pair of faulty boots to the manufacturer, this is the first test they’d perform, to check whether your claim is valid or if you’re just trying your luck.

- The best hiking socks: the comfiest socks tested on miles of tough terrain

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com