Is rock climbing dangerous? We look into the risks and how to manage them

Is rock climbing dangerous? We weigh up the hazards, describe the common risks and injuries and explain how to manage them to an acceptable level

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Is rock climbing dangerous? To the uninitiated, it certainly appears so. After all, we're talking about a pursuit that involves attaching a rope to yourself and scaling near vertical cliffs above drops that would potentially kill you if you fell without protection. So, those thinking about giving it a go would be well within their right to ask: is rock climbing dangerous?

However, millions of people rock climb worldwide, so surely it can't be that dangerous? It's a pretty standard activity on children's residential trips and, if you take a trip to a well known crag on a sunny day, you'll find loads of people attached to a rope, battling their way upwards.

So, to get to the bottom of whether or not rock climbing is dangerous, what the risks are and how you can control them, we've asked a couple of our climbing experts to put down their chalk bags and pick up their keyboards.

Is rock climbing dangerous?

Rock climbing is not considered a particularly high risk sport when practised safely.

Data suggests the odds of dying while rock climbing are well behind the likes of swimming, cycling and even running. However, the risks associated with rock climbing, as with many outdoor pursuits, do mean that an accident can be fatal.

A major element of climbing is learning to use protective gear safely. Once you have the knowledge and experience to do this, you'll be mostly in control of the hazards. Basically, you can manage the danger to an acceptable level.

This sets rock climbing apart from something like road cycling – you can't control what the person in the car heading towards you is going to do. Another example is mountaineering, where you can take all the precautions in the world and still be swept away by an unexpected avalanche. Dangers that you have little control over are called objective dangers. The main objective danger when rock climbing is rock fall and this can be managed, to an extent, by wearing a helmet.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

In short, the dangers present when rock climbing are mostly manageable. Rocks falling from above are countered by your helmet. A fall is countered by the fact you're attached to a rope, a belayer and you've placed protective equipment into the wall.

Of course, the hazards ramp up significantly if you were to remove protection entirely. This approach to rock climbing is free soloing and it's extremely dangerous.

Meet the experts

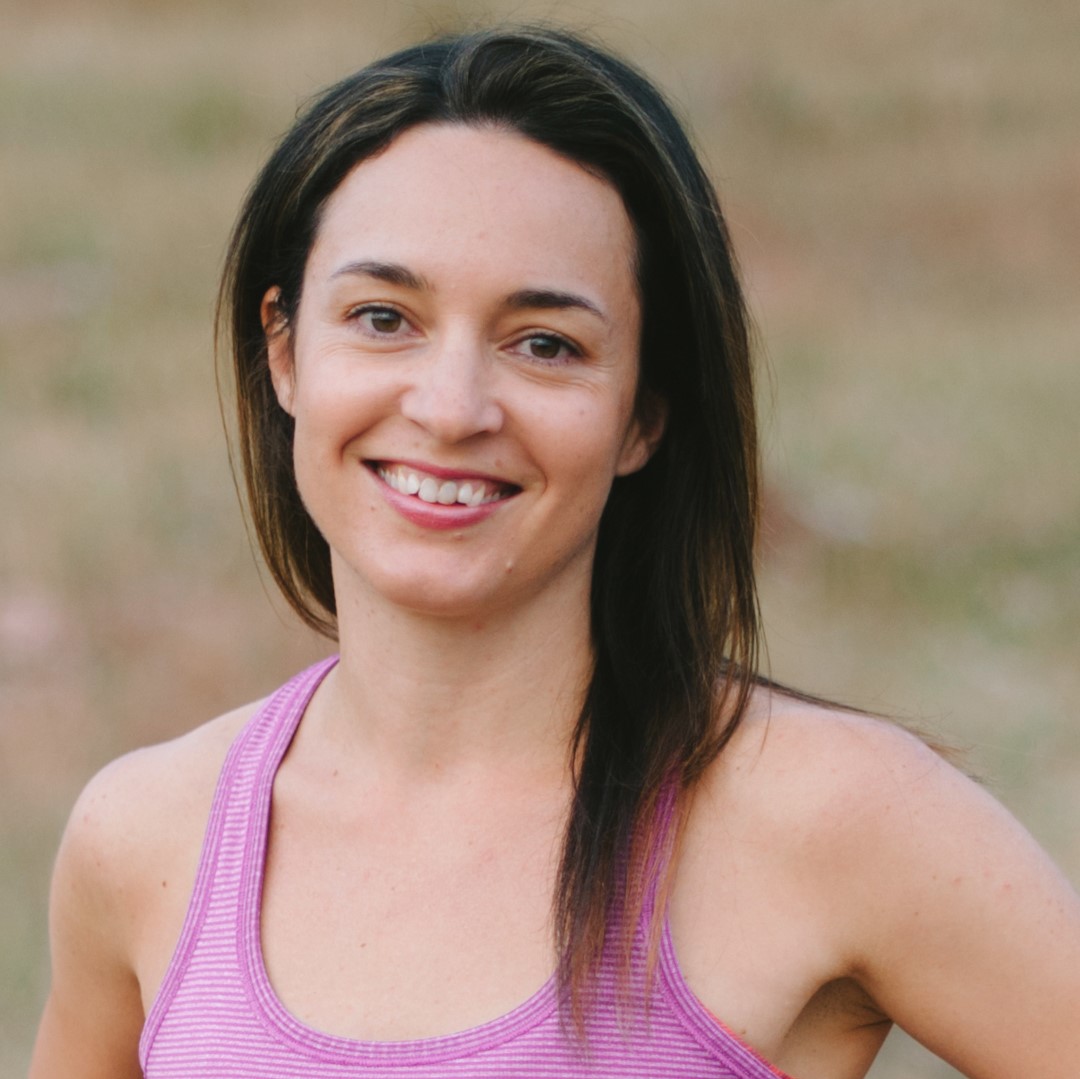

Julia spent a decade living in Vail, Colorado, where she became accustomed to climbing adventures in the mountains. Now back in her native Scotland, she's one of our leading experts on mountain adventure.

Former President of the London Mountaineering Club, Alex is passionate about exciting outdoor pursuits. He enjoys all forms of climbing, whether trad, sport, scrambling, alpine mountaineering or taking on snow-covered peaks in winter.

Today's best deals

What do the stats say?

- It's difficult to assess the stats as it's unclear how many people climb every year

- Added to this, not everyone accesses emergency care, while many injuries don't require such attention

- However, stats suggest only 2.5 per 1000 climbers end up in an emergency room

A common way of answering this question is to say that you’re more likely to get injured driving to the crag than when you’re on belay, but is that actually true?

While data on climbing fatalities is spotty, an article for the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that 40,282 patients in the US received emergency room treatment for rock climbing related injuries over an 18 year period. At 2,237 patients each year, that sounds like a lot, but if Statista is right in reporting that 10.28 million Americans went rock climbing in 2020, then the chances of ending up in the emergency room is about 2.5 per 1000 climbers or 0.25 per cent. Of course, it doesn't take into account more minor injuries that didn’t require emergency treatment or the sad fact that many Americans skip medical treatment altogether due to lack of insurance.

- Comparing climbing stats to driving is difficult as a much larger proportion of the population drive a car

Over on America’s highways, the CDC reports that in 2012 alone more than 2.5 million Americans ended up in the emergency room after a car crash while data on traffic related injury rates averages more than 800 traffic accidents per 100,000 population. But note that the number is per 100,000 population not per 100,000 drivers, so it’s not really possible to compare it with the climbing statistics. While there’s no argument that driving a car is one of the most dangerous things you do on a daily basis, its dangers are increased because most of us do a lot of it. A lot more than, say, rock climbing. And that’s where this comparison gets a bit fuzzy.

It’s easy to use insurance data, petroleum sales and traffic cams to estimate how many cars are on the roads and for how long, but we don’t truly know how many people go rock climbing and for how long and often they do it. We also don’t have data on those minor injuries sustained that don’t require medical intervention.

- According to some data, you're less likely to die when rock climbing than you are when swimming, cycling or running

- Rock climbing is not considered dangerous, though there are obviously risks involved

What makes more sense is to compare rock climbing to other sports, and this data gathered by Bandolier places the odds of dying while rock climbing well behind swimming, cycling and even running.

So, that was a long winded way of saying that rock climbing is not considered a particularly high risk sport and we really don’t know how it compares to driving a car, but there are definitely risks associated with rock climbing as there are any outdoor activity. Let’s face it, if there weren’t, we’d all be spider-manning up El Capitan tomorrow.

What are the risks of rock climbing?

According to a study by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, rock climbing accidents account for 10% of all mountain accidents and are rare but potentially fatal. The following are some of the common risks associated with rock climbing according to the study:

Minor injuries

The majority of climbing accidents lead to minor injuries such as scrapes from the rock and strained or torn ligaments. Climbers most frequently injure their extremities, not internal organs. The predominant portion of injuries are to the head, neck, chest and abdomen.

Falling

Falling is the most common cause of climbing injuries and it usually happens when you’re on the way up, not down. Lead climbers are at higher risk of falling than their partners. If you’re leading, you’re only as safe as the last piece of gear you placed, after all. This is why the start of a climb is often the most fraught, as that first bit of gear is often placed at a moderate height where a fall before it's correctly installed would still hurt.

Improper use of equipment

Of course, human error accounts for some rock climbing accidents, whether that’s not communicating with your partner properly, not tying in properly or not placing gear securely.

Gear failure

Though not common, it is possible for gear such as ropes, harnesses and anchors to fail. All of this gear should be purchased from reputable brands who are scrupulous in their safety manufacturing protocols.

Ankle injuries

Ankle injuries are common in bouldering, when you don’t land on the pad correctly, and also for lead climbers who fall before the first piece of gear is placed. These are usually fairly minor strains and sprains.

Snow and ice

Snow and ice covered surfaces increase the probability of falling, and the length of the falls.

Weather

Changing weather conditions always increase danger in the outdoors, whether that’s climbing a slick surface in the rain or dangerous conditions like lightning.

Falling rocks

This is one of those Five per cent of injuries involved someone being hit by a falling rock. This is one of the reasons why wearing a climbing helmet is so important.

How to stay safe when rock climbing

Just because rock climbing carries some inherent dangers doesn't mean you don't have a say in how safe you are. The following are some important steps you should take for staying safe when rock climbing:

- Take rock climbing skills classes with a trained professional

- Wear a helmet, even when on the ground

- Take good care of your ropes by cleaning them and inspecting your ropes and other gear regularly

- Wear well-fitting climbing shoes and harness

- Climb with people you trust and communicate properly on belay

- Check the weather before you go and stick to dry days for outdoor climbing

- Climb indoors when the weather isn’t playing ball

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.