What is trad climbing? Our expert guide to traditional rock climbing

What is trad climbing? We consider what separates trad from other climbing disciplines, along with where you can do it and what equipment is needed

- What is trad climbing?

- Comparison table

- How trad differs from other forms of climbing

- Where can you go trad climbing?

- What equipment is needed for trad climbing?

- Standard trad climbing kit

- Additional items when climbing in more remote regions

- What's the difference between single and multi-pitch climbing?

- What are trad climbing grades?

Just exactly what is trad climbing? When I started dipping my toes into mountaineering, I spent plenty of time around hardened rock climbers and started to hear the term, "trad". Having been regaled by tales of derring-do on remote sea stacks or of committing climbs on rocky crags, high up in some mountain range or other, I knew I wanted to know more.

It all sounded rather exciting, so just what is trad climbing? I'm here to give you the lowdown.

What is trad climbing?

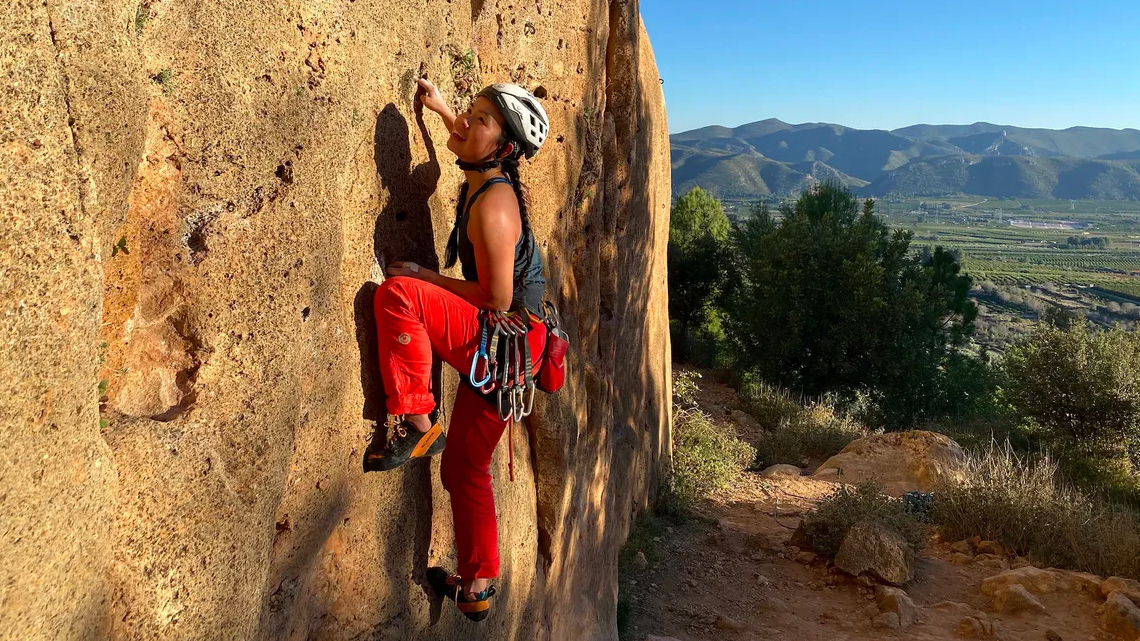

Trad climbing is the form of rock climbing where the lead climber installs their own protective gear into the rock as they progress up the crag.

Once happy, the leader clips a quickdraw into the gear and threads the rope through to protect themselves against a potential fall. The protective gear typically takes the form of cams, nuts and hexes placed into cracks in the rock. Typically, the second climber belays the lead from below. For the lead, placing gear takes time to master, not to mention stamina while on the wall, as they will often need to hold their position for some time while sorting the protection.

Once the lead reaches the top of the climb – or the top of that section of the climb, known as a pitch – they make themselves secure by tying into more protection. Once safely attached, they then belay the second climber. The second climbs the route, taking out the protection as they go and attaching it to their harness, thus reclaiming the gear. We've accumulated many hours sorting gear out at the end of a climbing weekend, as the cams, nuts and hexes inevitably end up on the wrong person's harness.

Comparison table

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Trad climbing | Sport climbing | Free soloing |

| Protection | Climbers place their own protection, such as nuts, cams and hexes, into the rock | Climbers clip themselves in to bolts that are already secured in the rock | Climbers ascend with no protection whatsoever |

| Specialist equipment | Cams, nuts, hexes, nut keys | Standard climbing kit | Very little |

| Where? | Technically, any crag where protection can be placed | Only designated sport climbing crags | Technically, anywhere |

| Partners? | Usually done in pairs | Usually done in pairs | Can be done alone |

Mastering trad climbing takes practice. To train for climbing, be it trad or sport, it’s worth spending a few days with an instructor, a more experienced friend or joining a climbing or mountaineering club. The obvious other thing to state is that you will need a climbing partner who you can put your trust in while on the crag.

Meet the expert

Former President of the London Mountaineering Club, Alex is passionate about exciting outdoor pursuits. He enjoys all forms of climbing, whether trad, sport, scrambling, alpine mountaineering or taking on snow-covered peaks in winter.

Today's best deals

How trad differs from other forms of climbing

- In sport climbing, the protection is already in place on the crag

- Free soloing is different to trad climbing, as it doesn't involve ropes or protection

- Trad techniques and skills are used in mountaineering and ice climbing

Trad vs sport climbing: it's about the placing of protection

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Trad climbing differs from the popular pursuit of sport climbing, where the protection is already installed, or bolted, into the rock. The challenge and skills involved in installing protection, finding the optimum line and juggling this with the actual act of climbing makes trad climbing so enthralling. It’s also a very pure approach to climbing, as – in theory – any crag, mountain or cliff can be tackled with a trad climbing approach. I found it more difficult to get into trad, as it's got a much steeper learning curve than sport, especially when leading a climb.

Trad vs free soloing: in free soloing, there is no protection

It also differs to Free soloing, an even purer and inherently risky approach to climbing that uses no ropes or protection to scale a route. The term was brought to mass audiences following the phenomenal success of 2018 film Free Solo, which followed the story of Alex Honnold's successful free solo of the Freerider route on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park.

Trad and moutaineering have similarities

There are many similarities between trad climbing and winter or alpine mountaineering. Mountaineers often face up against a mixture of steep rock, snow and ice that requires the use of a rope and protection in order to ascend safely. This is why skills gleaned during trad climbs are hugely useful to mountaineers. One of my main motivations to go trad climbing was to improve my rope skills with alpine mountaineering or Scottish Winter climbing in mind.

Then, there's ice climbing, which involves the placement of ice screws as protection in order to safely ascend.

Where can you go trad climbing?

- The beauty of trad climbing is that it can be done anywhere in theory

- Mountains, coastlines, gorges, quarries, outcrops, tors and escarpments all hold a host of possibilities

- Different environments and rock types bring different challenges

Unlike sport climbing, which is replicated at indoor climbing walls, trad climbing is a totally outdoor pursuit. From buttresses protruding from huge mountains and immense walls, like Yosemite’s El Capitan, to roadside crags and sea cliffs, there is an almost endless variety of trad climbing venues. Mountains, coastlines, gorges, quarries, outcrops, tors and escarpments all hold a host of possibilities, with a huge number of routes documented and graded in guidebooks or on the internet. I've been climbing in the Alps, in disused quarries and on natural crags in the Highlands and the flavor of each kind of venue is what keeps it interesting.

Different environments and rock types bring different challenges and character to a climb. Whether it's the granite of Yosemite, the grippy black gabbro of Scotland’s Black Cuillin, the famous gritstone of England’s Peak District or the high quartzite found in Morocco’s Anti-Atlas, the quality of the rock is often what attracts hosts of climbers to a region.

This is also true of the setting. While spectacular routes in mountainous regions make some climbers go dewy eyed, many are enthralled by the trad climbing found on the coast. The unique atmosphere and quality of sea cliff climbing, with the incoming tide goading you from below is a major draw for many. Some trad climbs require a boat to access, or a committing rappel just to begin the route.

What equipment is needed for trad climbing?

I steadily chipped away at the equipment required for trad climbing, getting a few bits at a time until I was in a position where I had everything I needed. Of course, the beauty is that, if you're new to it, you're likely to be seconding and there's a good chance your lead partner will already have most of the stuff needed. You don't both need everything. As a second, you may just need a helmet, a harness, rock boots and a belay device. Your partner may have the rest.

The equipment you need for trad climbing depends on the location of your chosen route. An easily accessed crag will require little more than your standard equipment and rack, whereas a venue deep in the heart of the wilderness will require you to take many hiking essentials along, due to the length of the walk-in unpredictability of the weather. Let’s start with the standard kit:

Standard trad climbing kit

Helmet – Head protection from a fall and from rockfall. Should be replaced immediately if damaged.

Harness – A padded climbing harness is most comfortable and a model with at least four gear loops and a central belay loop is recommended.

Rock boots – Tight fitting with sticky rubber soles that allow maximum precision and grip on the crag. Don’t be surprised if they’re uncomfortable to walk in, it’s not what they’re designed for. Easier routes can also be done in approach shoes, which occupy the middle ground between climbing shoes and hiking shoes.

Rope – For trad climbing, you should be looking for at least 50 meters in order to access the majority of single pitch routes.

Belay device – Either a manual breaking device or an assisted braking device that the rope is fed through the create friction

Carabiners – Oval or D-shaped metal hooks close with a gate – some have snap-gates, while others have screwgates.

Quickdraws – Usually between 10 and 25 cm in length, these consist of two snap-link carabiners linked by a tape sling.

Slings / webbing – Useful for making use of rock spikes, trees as runners or anchors.

Chocks – The different sized and shaped nuts and hexes that can be placed into the rock to create runners or anchors.

Camming devices – Known as cams, these are spring-loaded mechanical devices that can be fitted into cracks in the rock as runners or anchors.

Nut key – a superb piece of kit that makes removing awkwardly placed protection much less troublesome.

Additional items when climbing in more remote regions

- For more remote objectives, you'll need a pack and shoes you can hike in

- Depending on the nature of the walk in, you'll need all manner of hiking essentials

If you’re climbing in the backcountry, you will need to consider the environment, the weather and the length and technical difficulties of your walk-in – and therefore your walk-out.

You will need at least a daypack to carry your provisions: such as additional layers, waterproofs, navigation equipment, and food.

A headlamp is recommended in case you end up walking back in the dark (see our guide to the best headlamps for some good options).

For the hike to the crag, you may need a pair of the best hiking shoes or approach shoes, depending on your preference.

What's the difference between single and multi-pitch climbing?

- Single-pitch routes only take one rope length to complete

- Multi-pitch routes involve more than one rope length

- They are split into sections, or pitches

A single pitch climb is a route that only requires one rope length to complete. Trad climbers typically carry a rope of 50 meters or more to allow them to access the majority of single pitch venues. A single pitch approach represents ideal rock climbing for beginners, as the rope-work is more straightforward. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that single pitch routes are easier than multi-pitch climbs.

Multi-pitch climbs involve using more than one rope length and are therefore usually more committing. After each pitch, the lead climber has to find a suitable stance and secure themself with a solid anchor, before bringing the second up. From here, the process begins anew, as the lead climber forges onwards, with the second belaying from below. It’s not uncommon for climbers to switch between being lead and second on a multi-pitch climb.

Multi-pitch venues range from roadside crags that simply require more than one rope length, to massive routes in the mountains or on big walls that may involve in excess of a dozen pitches and require long walk-ins or a bit of scrambling to reach. This is where approach shoes come into their own.

What are trad climbing grades?

- Grades provide an idea of how challenging a climb will be

- Different countries have different grading systems

- Climbs are also often rated in terms of their quality

- Grades are always subjective and myriad factors can impact the difficulty of a given climb

For us, there’s something magical about a guidebook to a new region. All those crags and routes as yet unexplored. Spaces on the page awaiting the inky swish of a tick. Mountains that seemingly exist only in print and in our imagination, awaiting the moment they’re made tangible by first-hand experience and then committed to memory forever. We can hear the waves crashing at the foot of the sea cliff, even if we’re just sat at home, eyeing up the grades and ratings of future routes snaking up a face that’s routinely flogged by the elements.

Before a climb commences, you want to get an idea of what you’re in for. This is where a climb’s grade and rating come in. Ratings are usually given to indicate the quality of a climb. These are, of course, subjective and the format differs from guidebook to guidebook and website to website. Slightly more consistent are the systems used to grade the difficulty of a climb. Every discipline – from trad and sport, to bouldering and scrambling – has a grading system that indicates the level of difficulty, and these vary depending on where you are in the world. Our guide to climbing rating systems attempts to demystify any misconceptions across climbing’s myriad forms.

In terms of trad, there's the British Traditional Grading System, which begins by using adjectives (such as ‘Moderate’ or ‘Difficult’) to describe the severity of the climb as a whole and then reverts to an ascending numbered grade beginning with an ‘E’ (so, E1, E2, E3 etc.) once things get a little harder. At a certain point, this is combined with a technical grade, which describes the single most difficult move on the route. This is a number followed by a, b or c to signal nuances within the grade.

In America, the Yosemite Decimal System is used. This grades the difficulty of walks, hikes and climbs in ascending severity from 1 to 5, with 5 being rock climbs. The ‘decimal’ comes in to indicate the challenge of a given climb. So 5.1 is an easier climb than 5.2 and so on. The table below gives a rough indication of how the two systems relate to each other. However, climbing grades by their very nature are subjective and the difficulty of a climb is prone to many factors. The table should not be taken as a hard-and-fast comparison.

| British trad grade | British technical grade | US grade |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate (Mod) | Row 0 - Cell 1 | 5.1 / 5.2 |

| Difficult (Diff) | Row 1 - Cell 1 | 5.2 / 5.3 |

| Very Difficult (VDiff) | Row 2 - Cell 1 | 5.2 / 5.3 / 5.4 |

| Hard Very Difficult (HVD) | Row 3 - Cell 1 | 5.4 / 5.5 / 5.6 |

| Mild Severe | Row 4 - Cell 1 | 5.5 / 5.6 |

| Severe (Sev) | Row 5 - Cell 1 | 5.5 / 5.6 / 5.7 |

| Hard Severe (HS) | Row 6 - Cell 1 | 5.6 / 5.7 |

| Mild Very Severe | 4a / 4b / 4c | 5.6 / 5.7 |

| Very Severe (VS) | 4a / 4b / 4c | 5.7 / 5.8 |

| Hard Very Severe (HVS) | 4c / 5a / 5b | 5.8 / 5.9 |

| E1 | 5a / 5b / 5c | 5.9 / 5.10a |

| E2 | 5b / 5c / 6a | 5.10b / 5.10c |

| E3 | 5c / 6a | 5.10d / 5.11a / 5.11b |

| E4 | 6a / 6b | 5.11b / 5.11c / 5.11d |

| E5 | 6a / 6b / 6c | 5.11d / 5.12a / 5.12b |

| E6 | 6b / 6c | 5.12b / 5.12c / 5.12d / 5.13a |

| E7 | 6c / 7a | 5.13a / 5.13b / 5.13c |

| E8 | 6c / 7a | 5.13c / 5.13d / 5.14a |

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com