How to survive a night on a mountain

Think you could survive a night on a mountain? We speak to a mountain guide and member of Lochaber Mountain Rescue team to find out exactly what you need to do to stay alive

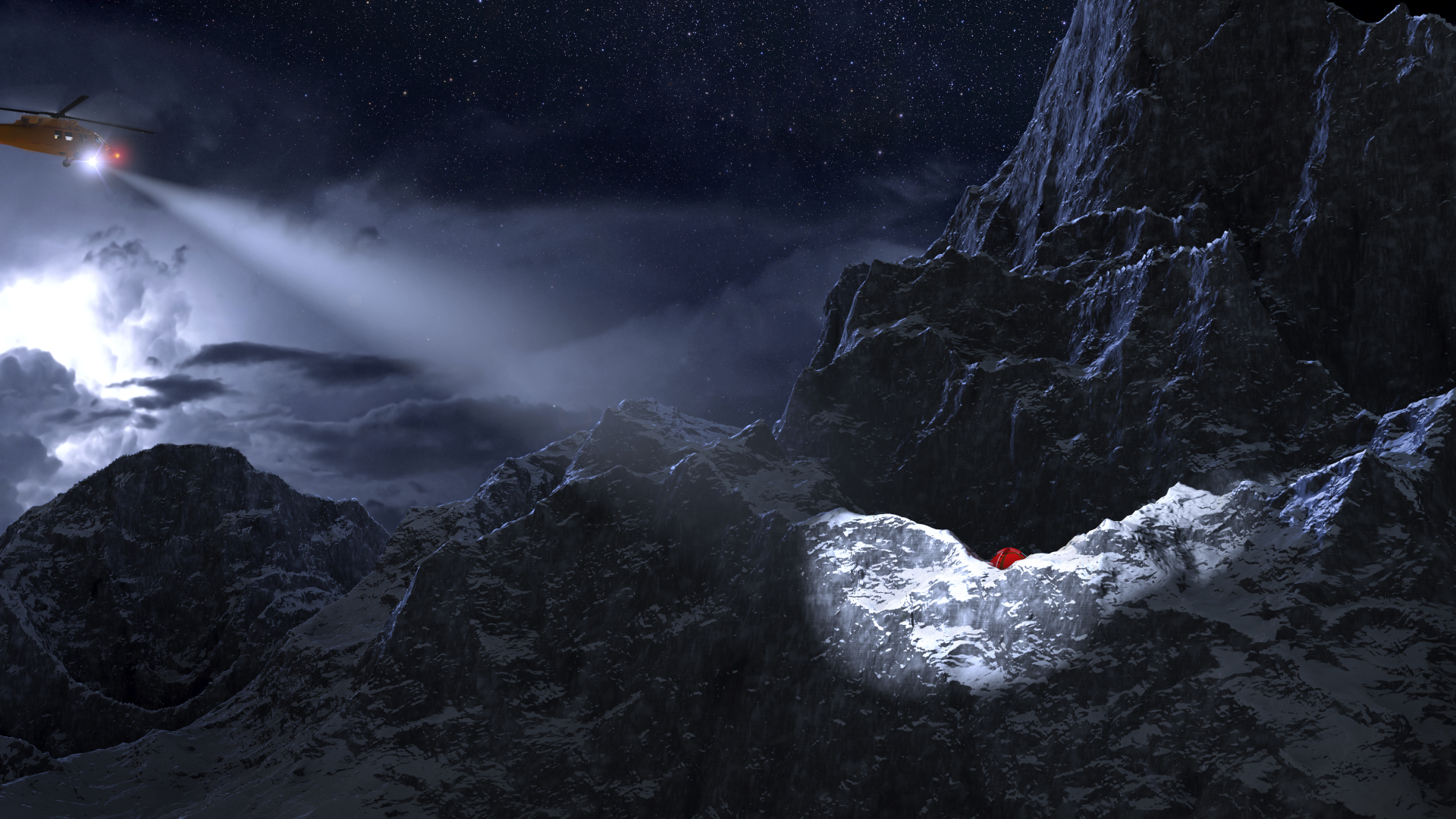

You’ve been walking all day and you’re dog tired. The light is almost gone and you realized some time back that you’ve made a navigational mistake. You’re not where you thought you were, and you’re probably spending the night out here, in the dark and the freezing cold. So, how do you survive a night on a mountain?

This is a question I’ve thought about a lot as a hiker, and one I know you might have too. Many of us who live for the outdoors have pictured ourselves getting into trouble on an adventure, and hunkering down in some convenient burrow until the chopper shows up like it does in the movies to whisk us to safety (cut to the the scene of you in a hospital bed, surrounded by pretty nurses and smiling family members).

I’m aware, however, from having many friends who have spent unplanned nights in the wild, that the reality is nothing like this Hollywood fantasy. Once the sun sets, it can get unimaginably cold in alpine areas, where conditions can change quickly, and a flask of hot chocolate and a pair of insulated hiking boots aren't going to be enough to get you through.

To get a more realistic idea of how to survive a night on a mountain, I spoke to mountaineer Mike Pescod, owner of Abacus Mountain Guides. It’s easy to think that everyone who gets rescued from a mountain is a novice who went up in flip flops, but in reality, the reverse is probably true. Those who hike in flip flops don’t tend to get very far, while expert climbers like Pescod are more likely to get swept up in an avalanche, which is exactly what found him at the bottom of an ice fall he’d just climbed back in 2004 with a broken back, pelvis, ankle and a few ribs. He was ice climbing at Nevis Range, a ski resort which is just a few miles outside the town of Fort William in Scotland, but it still took mountain rescue over five and a half hours to reach him.

Pescod’s experience encouraged him to join the Lochaber Mountain Rescue team, and in addition to his guiding work he now spends a lot of time helping other hikers and climbers in distress, which doesn’t involve swooping in, plucking folk off the mountainside and depositing them safely at home. Here he explains that the reality of surviving a night on a mountain involves a lot of preparation, effort and perseverance on your part, and that of course starts with you leaving details of where exactly you're going and what time you plan to return with a trustworthy person. Here’s how to survive a night on the mountain, from an expert.

1. Carry the right kit

Surviving a night on a mountain starts with planning as though you’re going to spend the night on a mountain, even if you’re only intending on doing a half day hike.

When Pescod woke up about 10 minutes after being knocked unconscious, his quick-thinking clients had already contacted mountain rescue, communicated their location and chopped out a ledge to stabilize the ice around them. All he had to do was lie and wait to be rescued, which was pretty convenient since he couldn’t move. It was pretty much a rescue dream come true.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

But it wasn’t that simple. When one of the first two members of the rescue team went back to get some gear, he was blown off the summit and fell over 300ft. Now he needed rescue and Pescod took up second position in the queue of priority.

Both men were rescued, but the point is, if you get stuck or lost on a mountain, it’s going to take mountain rescue hours to reach you, in the best of conditions. Once those temperatures drop below freezing, if you want to stand any chance at all of surviving the night, you need to have the right clothing.

Pescod advises dressing in your typical hiking layers for your day – that’s a base layer, mid layer like a fleece jacket and a shell or insulated jacket over the top. Forget about down, which won’t keep you warm once it’s wet, and choose synthetic materials and merino wool. Then bring enough spare warm clothing, hats and gloves to keep you going for another six to 12 hours.

In addition, he says, pack an emergency dry bag inside your backpack that’s only for emergency items. This dry bag doesn’t come out during the day and contains a an emergency shelter, a synthetic insulated jacket and your spare clothing, including a dry base layer. When you realize you’re spending the night outdoors, pull out the dry bag and dig around for that base layer, says Pescod.

“The thing I do when I go climbing, or if I'm out camping, is I'll have a spare base layer shirt inside my rucksack, kept dry. So when I get to my camp, I'll strip down, put my dry shirt on and then the wet ones on top. So I feel great, I feel dry, I feel like I'm cozy, but I'm also drying out the wet ones with my body heat.”

Pull on all of your other spare clothes and now you’re wearing warm, dry fabric next to your skin and your wet clothes are drying. Next up, pull out your group emergency shelter. Emergency shelters, or bothy bags, are made of material like nylon and polyester and are windproof and waterproof. They have no poles and come compressed into stuff sacks a lot like your best sleeping bag, and can be pulled out and quickly erected into a rectangular shelter that several people can hide inside to fend off wind and rain. They can weigh as little as a pound, or even less, and make the difference between life or hypothermia.

“They make such a difference, they're amazing, because when it's minus 10 outside, it can go up to zero inside and you cut out the windchill. There's no windchill inside, so from feeling like minus 20 outside, you're feeling zero, which is just fine,” says Pescod.

In addition to shielding yourself from the brutal assault of the air temperature, you’ll lose a lot of heat from the ground, so Pescod advises insulating yourself from the cold ground by sitting on your backpack, huddling together with anyone that you’re with, and eating and drinking to stay warm.

2. Keep moving

We all tend to think that once night falls, the safest thing you can do is stay put until the morning. In Pescod’s incident, he had no choice but to lie still and wait for rescue (another argument for wearing the right clothing) but if you’re not immobilized, he says it’s usually preferable to keep moving.

“If you're not injured, don't just think that because it's gone dark, you can't move. I think for some people, there's quite a fear of moving around in the dark, but you can do it,” says Pescod, who explains that you can learn to navigate in the dark just like you can navigate in whiteout conditions – by taking a compass bearing and pacing out your distance.

“Have a good torch, definitely, and just kind of keep working away at it. It's better to keep on moving than just to sit down and wait for a rescue, or wait for the next day, because you stay warm. As soon as you sit down for half an hour, you're really, really cold.”

But where do you move to? Well, if you’ve absolutely no idea where you are, and you’ve communicated your location to mountain rescue who have told you to stay put, stay put and walk in small circles or do some jumping jacks. But let’s say you’ve made a navigational mistake and gone off the wrong way. Chances are that when you realize what you’ve done, if you’re already descending the mountain, you might persevere and try to keep pressing on downhill, assuming at some point that you’ll reach a road at the bottom. After all, the last thing you want to have to do is turn around and climb back uphill after such a grueling day. That, however, is false logic and often results in accidents happening, according to Pescod.

“The more secure way would be to turn around and walk back uphill to the path that you should have been on, and follow the regular way down,” he advises.

In fact, when you call mountain rescue – which Pescod says you should do very soon after realizing you’re lost or stuck – they might not actually tell you to stay put while they come and get you. Instead, they might talk you through your own self-extraction.

“The rescue team can help out, but they don't instantly jump into the cars, go racing to the base of the mountain and come up with blue lights flashing. If there's a simple solution, then they'll tell you on the telephone, and they'll try and help you out. So many times we've talked to people down by guiding them remotely.”

3. Find (or make) shelter

So surviving a night on a mountain doesn't necessarily mean building a shelter and weathering out the storm, as you might have assumed, but still there are a couple of scenarios where you wouldn’t keep moving and try to navigate your way down. First, if mountain rescue has told you to stay put till they arrive, stay put, otherwise they won’t be able to find you. Then, as in Pescod’s experience, you may be injured and unable to go very far, or the weather conditions might make further travel impossible or dangerous. If you find yourself in either predicament, and you’re up above treeline or on a ridge, you might want to move out of the wind.

“Windchill is quite a major factor, so you might move a little bit to get out of the wind if you're in an unexposed place. You want to get out of that and find some shelter somewhere. So you might well move just a little bit to get down off the ridge crest, down off the side a little bit, or try and find a little hollow somewhere just out of the wind.”

Go a little lower in elevation and look for gullies, but avoid cliffs, cornices and areas of blown snow on slopes of more than 30° – in these areas you might be subject to avalanche conditions. If you’re carrying an ice axe and in snowy conditions, you can make your own shelter.

“You can dig holes in the snow in areas where the snow blows over and gets quite deep. Just with an ice axe and about half an hour or 45 minutes you can dig a hole that's big enough to get inside. That can be brilliant. Again, you get out of the wind, and warm up relative to the outside temperature.”

Don’t, however, just start digging out into the snow beneath your feet, Pescod warns, because then snow is going to be blown down on top of you. Find a fairly vertical snowbank and start digging in and upwards, so that once you’re tucked inside it’s just your feet that remain a little exposed.

If someone in your group is injured and unable to move to a more sheltered spot, you can fashion a temporary stretcher out of an orange emergency survival bag and two trekking poles to help carry them, though you’ll only be able to go a few hundred feet at most. In snowy conditions, you can drag them on the plastic to a more sheltered place.

4. Use a good old-fashioned whistle

There’s quite a bit of fancy tech these days that Pescod advises you to carry and know how to use, and we’ll get to that in a moment, but the most basic piece of technology that might save your life is one that can be easily overlooked in a world of RECCO reflectors and GPS watches.

“People forget about whistles but they're so effective. The sound of a whistle goes for a very long way.”

If you don’t remember from summer camp, the international distress signal is six loud blasts, wait a minute, then six more blasts and wait a minute. If you can’t remember that, Pescod says, just keep blowing a whistle fairly persistently

“Very often there's somebody around somewhere, so they'll come and investigate.”

Similarly, if the rescue team is trying to pinpoint your exact location, you can help them out by blowing your whistle until they're quite close to you. Just stop blowing once they arrive or they might change their minds and leave you there. Hiking whistles are a lightweight and affordable piece of kit, and don’t forget that all Osprey backpacks come equipped with a built-in whistle in the chest strap.

On a related front, you can use your best headlamp or flashlight to flash signals in the dark, allowing a rescuer or another hiker to pick up your signal in the dark.

5. Embrace technology

Finally, we get to the tech. Many hiking purists eschew GPS technology and phones over navigational equipment like a map and compass, but Pescod is one of several mountain rescue guides I’ve interviewed who believes that in addition to those important traditional tools, emergency technology definitely holds some real value in a survival situation.

“It's great, the technology is getting smaller and more compatible with everything else,” he says.

Personal locator beacons, which Pescod describes as “like a big, red emergency button that just sits in your backpack and doesn’t do anything unless something’s gone wrong,” can be picked up for a couple of hundred dollars, and allow you to send out an emergency alert to the satellite system even if you have no phone signal. Your message will bounce back down to Texas, where a 24-hour command center will communicate your whereabouts anywhere in the world to your nearest rescue services (again, don’t move once you’ve pinged them).

A similar, but more expensive, device with more functionality is the Garmin InReach, a two-way satellite messenger which allows you to communicate with your rescuers via text without cell service, and the new iPhone has in-built satellite emergency function to help you get a distress signal out, which hasn’t been properly tested yet by mountain rescue, but Pescod says is encouraging. After all, we might all balk at the idea of spending $200 on a locator beacon we may never use, but $1300 for the new iPhone? No problem.

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.